Sigismund Bell in Art and Literature

Andrzej Włodarek

translation: Kinga Stoszek

After the loss of Poland’s independence, during the existence of the Free City of Cracow (1815-1846), Kraków began to be perceived by Poles in all annexed territories as the spiritual capital of Poland and a treasury of national memorabilia. In this context, the Sigismund Bell, as a witness to momentous occasions in the history of Poland, acquired the status of a national symbol. This role was strengthened by stories that it was cast from cannons captured in the Battle of Orsha in 1514 or in the Battle of Obertyn in 1531. According to legend, at the sound of the Sigismund Bell on Christmas Day, Easter and Midsummer Eve, Polish kings wake up from their sleep and gather in the underground Wawel Hall, and knights sleeping at Giewont are also awakened to the sound of the bell. The Sigismund Bell found its way not only into legends and fairy tales, but also into popular culture and became the motif of proverbs and sayings. From the mid-19th century, a saying was known in the area of Kraków: “When they ring the Sigismund Bell at Christmas, you can hear it “until Easter” [in Polish: “all the way to Wielkanoc” – a village whose name literally means “Easter”]. The saying, therefore, was not, about the duration of the sound of the bell, but about the range of its audibility. Wielkanoc is a village considerably removed from Kraków, situated in the Miechów area, and thus during the Partitions of Poland, in the Austrian partition. Interest in the Sigismund Bell was also heightened by major national events, on the occasion of which the bell was rung, as well as technical problems and repairs to the clapper or ties. Of course, all this was reflected in the literature, poetry and fine arts of the time.

The earliest poetic work written about Sigismund Bell is a poem by the Kraków poet Edmund Wasilewski (1), Dzwon wawelski. Wyjątek z poematu, a poem about the bell published in 1841 was also written by the poet and playwright Lucjan Rydel (1870-1918), who included it in his Przewodnik ludowy po katedrze wawelskiej [Guide to the Wawel Cathedral]. The Zygmunt bell plays a unique role in the works of Stanisław Wyspiański. In Wesele [The Wedding], court jester Stańczyk, concerned about the fate of his homeland, describes the hanging of a bell on a tower and its first ringing. In Wyzwolenie, Sigismund Bell itself calls out to the nation and announces resurrection. Also in Akropolis, Zygmunt’s voice is heard in the play’s climactic scene. The motif of Sigismunt Bell also appeared in the works of Wincenty Pol (1807-1872), Teofil Lenartowicz (1822-1893), Maria Konopnicka (1842-1910) and other poets and writers. One of Kraków playwrights Konstanty Krumłowski (1872-1938) is the author of the patriotic song Jak długo w sercu nasze, the second stanza of which begins with the familiar words: “Jak długo na Wawelu / Zygmunta bije dzwon[…]” [As long as the Sigismund Bell tolls at the Wawel Cathedral, it tolls in our hearts]. According to various sources, the song was written at the end of the 19th century or around 1920. Already in the 1920s, this text became an inspiration for the anthem of the “Wisła” football club, which begins with the famous phrase.

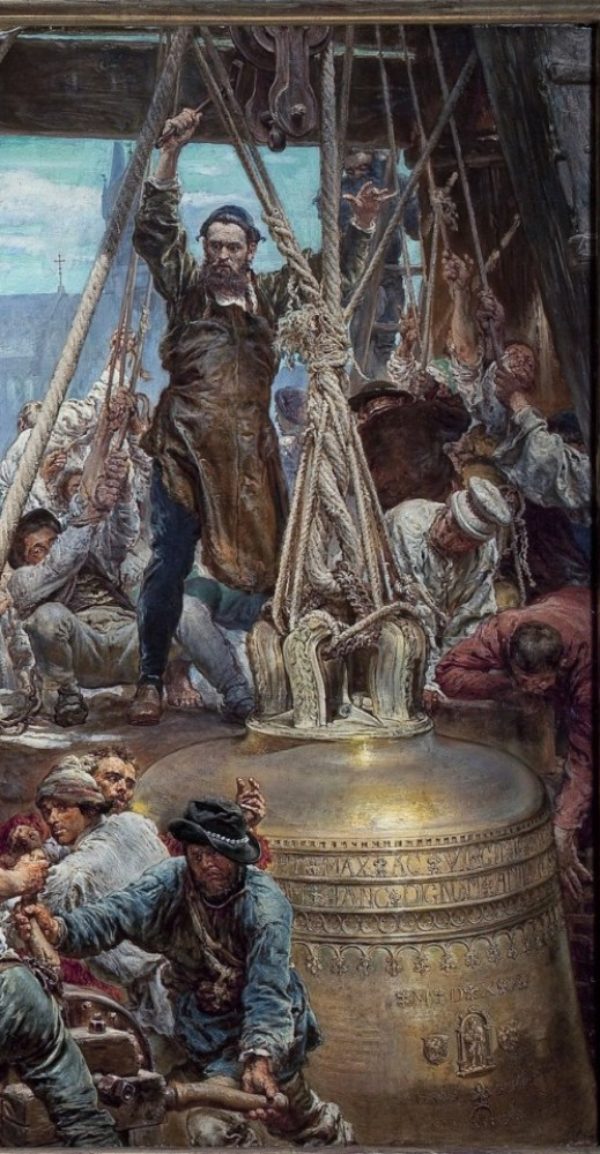

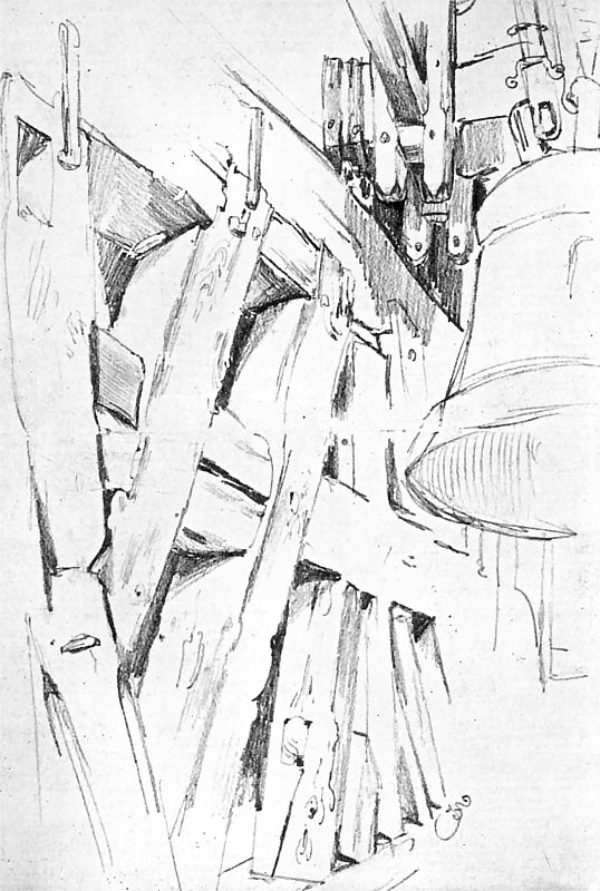

The Sigismund Bell was also a rewarding and attractive motif for painters. Sigismund had to appear in the works of the leading Polish painter of the historicist era, Jan Matejko (1838-1893). As early as in 1861, he made a sketch for a monumental painting Dzwon Zygmunta [The Sigismund Bell]. Unfortunately, this work was not realised, and the sketch itself has not survived. In 1862, the painter started work, which was not completed until 1883, on a small picture of Sigismund the Old listening to the Sigismund Bell. The king is shown in the company of courtiers, in the light of the bell aperture on the first floor of the Zygmunt tower, with the swaying bell visible above their heads. This imaginary scene of symbolic significance was meant to encourage reflection on the “Sigismund times” and the power of the past.

The best known depiction of the Sigismund Bell, permanently etched into the collective consciousness, is Jan Matejko’s painting The Hanging of the Sigismund Bell at the Cathedral Tower in 1521, painted in 1874. It presents three episodes from the history of the creation of the bell against the background of the buildings on Wawel Hill. In the right part of the composition, in the foreground, the painter has placed the scene of the bell being taken out of the pit in which it was cast. The left-hand part of the painting depicts the royal court with King Sigismund the Old and Queen Bona in the middle, watching the efforts of the craftsmen. In the middle of the composition, we see a bishop in pontifical attire, surrounded by assisting clergymen. With his right hand raised, he blesses the bell and the working people. In 1875, the painting was shown at exhibitions in Kraków, Vienna and Paris. In 1878 it was presented in Warsaw and again in Paris at the World Exhibition. At the same time it was popularized thanks to reproductions and engravings published in “Tygodnik Ilustrowany”, “Kłosy” or “Wędrowiec”. Today, the painting is exhibited in the National Museum in Warsaw. However, in the Matejko House, a branch of the National Museum in Kraków, studies of drawings of the Sigismund Bell, made by Matejko during preparations for the painting’s composition, are kept. Sigismund was also immortalised by the painter and book illustrator Piotr Stachiewicz (1858-1938) in a painting entitled The Sigismund Bell. Today, this painting is held in the collection of the Stanisław Fischer Museum in Bochnia. The same motif, similarly depicted, also appeared in the work of the painter and watercolourist Stanisław Tondos (1854-1917), and was reproduced on postcards.